Last Updated on May 6, 2025

The most famous gold coins have achieved legendary historical status not merely for their precious metal content, but for the historical moments they represent, their artistic beauty, and the cultural significance they embody.

Each coin carries multiple layers of meaning:

- as a financial instrument

- as a political statement

- as an artistic canvas

- as a tangible connection to history.

The yellow metal has been a store of value, a unit of account and a circulating currency for thousands of years. Despite a lot of disparagement gold remains a pillar of the global monetary system.

These gold coins have transcended their utilitarian purpose as money and are powerful symbols of wealth, art and cultural heritage. They offer unique insight into the civilizations that created them and the development of human societies.

My personal favourite is the Solidus because I am fascinated by the idea of Constantine issuing it to try and brink Rome back from the brink. But then Rome utlimately fails yet the Solidus survives. It is a classic tale about the enduring power of gold.

| Bonus: Click here to find out 3 additional famous but forgotten gold coins. |

1. The Lydian Stater: The World’s First True Precious Metal Coin

History of the Stater

The Lydian Stater holds the distinguished position as the world’s first standardised gold coin. It was minted around 600 BCE in the kingdom of Lydia (located in modern-day Turkey).

Although technically the first Staters were not actually gold, rather they were electrum, a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver.

The Lydians’ decision to create standardized coins was transformative for commerce. Before the Stater, trade relied on barter systems or inconsistent metal weights that required verification for each transaction.

The Lydians recognized that a standardized, government-backed currency could facilitate smoother commercial exchanges across their kingdom, which strategically controlled important trade routes between Asia and the Mediterranean.

Standardising the coinage and stamping it with the seal of the sovereign was a significant development in monetary history.

The Lydian empire flourished after introducing this currency. The wealth generated through more efficient trade helped fund impressive architectural projects and military campaigns that expanded Lydian influence until the Persian conquest under Cyrus the Great around 546 BCE.

Design

The Stater’s design was simple yet revolutionary for its time.

The obverse (front) featured a distinctive lion’s head, the symbol of the Lydian royal house, rendered in a stylized profile that demonstrated remarkable artistic skill for the period.

The reverse side initially bore simple punch marks that served as an authentication feature. These marks evolved over time, becoming more elaborate as minting techniques advanced.

Unlike modern coins with detailed inscriptions, the Stater contained no writing or numerical denomination. Its value was inherent in its standardized weight and metal composition, which the royal authority guaranteed. The electrum composition was eventually standardized to approximately 75% gold and 25% silver, though this ratio varied in early examples.

Why the Stater is Famous

The Lydian Stater’s fame rests on its revolutionary historical significance as one of humanity’s most important financial innovations—the concept of standardized currency backed by governmental authority.

The Stater established essential principles that remain central to modern monetary systems: standardization, official authentication, and portable stored value. By eliminating the inefficiencies of barter and unstandardized precious metals, it accelerated commerce and wealth creation throughout the ancient Mediterranean.

Numismatists and historians regard the Stater as the critical bridge between primitive money (such as cowrie shells or metal ingots) and modern coinage. Its influence spread rapidly across the ancient world, with Greek city-states, the Persian Empire, and eventually Rome adopting and refining the Lydian innovation.

2. The Croeseid: The First Pure Gold Standard

History of the Croeseid

The Croeseid was introduced around 550 BCE by King Croesus of Lydia, whose immense wealth became so legendary that his name remains synonymous with extreme affluence even today (“as rich as Croesus”).

While his father Alyattes had pioneered the concept of standardized coinage with the electrum Stater, Croesus transformed the global monetary landscape by introducing the world’s first pure gold coin and bimetallic currency system.

The development of the Croeseid marked a pivotal technological breakthrough in metallurgy. Lydian craftsmen had discovered refining techniques to separate electrum into its component metals—pure gold and silver—allowing for control over the coin’s precious metal content.

This innovation enabled Croesus to mint in gold rather than electrum. He also establish a fixed exchange rate between gold and silver coins (typically 1:10), creating the world’s first truly sophisticated monetary system.

Croesus’ reign represented the apex of Lydian wealth and power. His kingdom controlled lucrative trade routes connecting Asia with the Greek world and possessed rich natural resources.

Croesus’ prosperity was short-lived. as the Lydian Empire was defeated by the Persians an absorbed into their empire. However, the Persians wisely continued using Croesus’ monetary system.

Design

The Croeseid represented a significant artistic and technical advancement over earlier coinage. Made of nearly pure gold (approximately 98% purity), these coins featured a weight standard of approximately 8.1 grams for the standard unit.

The obverse design displayed confronting heads of a lion and bull—powerful symbols representing the Lydian royal house. The lion, with its detailed mane and fierce expression, embodied royal strength, while the bull symbolized fertility and economic prosperity.

Unlike the earlier Staters with their simple punch marks, the reverse of the Croeseid featured two square incuse punches of different sizes, creating a distinctive and recognizable pattern.

The coins bore no inscriptions or marks of value—their worth was inherent in their carefully standardized weight and purity. This absence of text reflects the pre-literate nature of currency at this time; the symbolic imagery and consistent physical properties provided all the authentication their users required.

Why the Croeseid is Famous

The Croeseid holds a place in monetary history as the world’s first pure gold coin and the cornerstone of the first bimetallic currency system.

Beyond its economic significance, the Croeseid represents the pivotal moment when coinage evolved from a regional Lydian curiosity into a universal concept adopted across civilizations. The Persian Empire, which conquered Lydia, recognized the brilliance of Croesus’ monetary innovation and continued to produce similar coins, spreading this system throughout their vast territories from Egypt to India.

The famous Greek historian Herodotus specifically mentioned these coins in his writings, helping cement their legendary status. The tale of Croesus showing his vast treasury to the Athenian lawgiver Solon, who cautioned that wealth alone doesn’t guarantee happiness, became one of antiquity’s most repeated moral lessons.

For modern collectors and museums, authentic Croeseids represent the holy grail of ancient numismatics. Their historical significance, artistic merit, and extreme rarity combine to make them among the most coveted artifacts from the ancient world.

3. The Persian Daric: The Archer’s Gold

History of the Daric

The Persian Daric emerged around 515 BCE under the reign of Darius I (522-486 BCE), one of the greatest rulers of the Achaemenid (or Persian) Empire.

Following the Persian conquest of Lydia under Darius’ predecessor Cyrus the Great, the empire inherited not only vast mineral wealth but also the revolutionary monetary system pioneered by King Croesus. Darius recognized the value of standardized coinage for governing his vast territories stretching from Egypt to the Indus Valley.

The name “Daric” derives directly from Darius himself, highlighting how closely these coins were associated with imperial authority. Darius implemented these coins as part of a comprehensive economic reform that included standardized weights, measures, and taxation systems throughout the empire. This created economic integration across the ancient world’s largest empire.

Persian Darics maintained their consistent weight and purity standards for nearly two centuries, circulating widely not only within Persian territories but also throughout the Mediterranean world. They became particularly prevalent in Greek territories, where they were both admired and resented as symbols of Persian wealth and power.

The production of Darics continued until Alexander the Great’s conquest of Persia in 330 BCE, when they were replaced by coins bearing Alexander’s image—marking a symbolic transfer of imperial authority.

Design

The Daric featured a remarkably consistent design throughout its two-century history. These coins were struck in high-purity gold (approximately 95-98% pure) and weighed a consistent 8.4 grams, slightly heavier than their Croeseid predecessors. Their reliability in weight and purity made them trusted throughout the ancient world.

The obverse displayed the iconic image of the “Persian Archer”—a bearded royal figure in a half-kneeling posture, wearing a crown and royal robes, holding a bow in one hand and typically a spear or arrows in the other. This figure is traditionally identified as the “Great King” of Persia, though it represents a generalized royal image rather than specific portrait features of individual rulers, as would come later with the Romans. The archer embodied the Persian military ethos and referenced the elite status of archery in Persian culture.

The reverse side featured a simple irregular incuse punch mark—a manufacturing artifact from the minting process that served as an authentication feature. Unlike Greek coins of the same era, which rapidly evolved to include elaborate reverse designs, the Persians maintained this minimalist aesthetic for centuries, emphasizing continuity and stability.

Darics bore no inscriptions or numerals—the royal archer image itself served as the imperial guarantee of the coin’s authenticity and value. This design choice reflected the multilingual nature of the Persian Empire.

Why the Daric is Famous

As the official gold currency of the ancient world’s largest empire, the Daric profoundly influenced international trade and finance across three continents. The coin’s exceptional consistency in weight and purity established new standards for monetary reliability that influenced all subsequent coinage systems.

The Daric’s iconic archer design represents one of history’s earliest examples of political propaganda through currency. By displaying the Persian king as an archer—the most elite Persian military class—these coins projected imperial power and legitimacy throughout the realm and beyond. This established a precedent for using coin imagery as expressions of state ideology that continues to modern times.

4. The Roman Aureus: The Imperial Gold Standard

History of the Aureus

The Aureus emerged as Rome’s principal gold coin around 82 BCE during the tumultuous final decades of the Roman Republic. While early Roman currency had relied primarily on silver and bronze, military expansion brought unprecedented wealth into Roman coffers, particularly from conquered territories in Spain, Gaul, and later Egypt, which possessed rich gold deposits.

The Aureus was first minted in large quantities by Julius Caesar in 46BC during the late Roman Republic, who standardized its weight at approximately 8 grams.

However, it was Caesar’s great-nephew and heir, Augustus (27 BCE-14 CE), who truly established the Aureus as the cornerstone of imperial Roman currency after becoming Rome’s first emperor.

For over three centuries, the Aureus served as the highest denomination in Roman currency, facilitating international trade, funding military campaigns, and symbolizing imperial prestige. While the silver denarius was more widely used as day to day currency, the aureus was the preferred medium for large transactions.

The Aureus remained the standard gold coin in the Roman monetary system until it was replaced by the Solidus in 312AD.

Design

Unlike many ancient coins with static imagery, the Aureus’ appearance continuously evolved, creating a numismatic chronicle of Roman history spanning over three centuries.

The obverse typically featured a portrait of the reigning emperor (or occasionally other imperial family members), accompanied by an inscription identifying their name and titles.

The reverse designs varied widely, reflecting imperial priorities, achievements, and propaganda messages. These reverse designs were accompanied by inscriptions that reinforced imperial messaging, often proclaiming military victories, promising prosperity, or highlighting the emperor’s religious piety or generosity through public works and games.

Why the Aureus is Famous

As Rome’s premier gold coin during the empire’s zenith, it embodies the economic power and cultural influence of antiquity’s greatest civilization.

For historians and archaeologists, the Aureus provides invaluable insights into Roman political history, economic conditions, and artistic developments. The chronological series of imperial portraits on these coins constitutes the ancient world’s most comprehensive “photographic” record of rulers, while reverse designs document historical events, architectural achievements, and evolving imperial ideologies in a form that has survived when other records perished.

The Aureus’ legacy extends beyond its material value—it established design traditions and technical standards that influenced Western coinage for two millennia. From medieval gold coins to modern commemorative issues, the fundamental concept of currency bearing a ruler’s portrait and state symbols traces directly back to innovations perfected on the Roman Aureus.

5. The Solidus: The Thousand Year Gold Standard

History of the Solidus

The Solidus emerged as a revolutionary monetary innovation in 309 CE. Emperor Constantine the Great introduced it as part of sweeping economic reforms designed to stabilize the Roman Empire after decades of currency debasement and financial chaos.

The name “Solidus” derives from the Latin word meaning “solid” or “reliable,” reflecting its intended purpose as a dependable store of value during turbulent times.

Constantine established the Solidus at 4.5 grams of virtually pure gold (approximately 98%) with an initial value of 275,000 increasingly worthless denarii. Unlike the Aureus it replaced—which had suffered progressive weight reduction under previous emperors—the Solidus was minted with remarkable consistency.

This weight standard was maintained with extraordinary precision for over seven centuries, making it perhaps history’s most stable currency.

When Constantine moved the imperial capital to Constantinople (modern Istanbul) in 330 CE, the Solidus became the foundation of what would evolve into the Byzantine Empire’s monetary system. As the Western Roman Empire collapsed in the 5th century, the Solidus continued circulating in the Eastern Empire, becoming the primary gold currency throughout the Mediterranean world and beyond.

The Solidus’ influence expanded far beyond Byzantine borders. Arab caliphates based their gold dinars on its weight standard, while Western European kingdoms such as the Merovingians and Visigoths created imitative gold tremisses (one-third solidus) bearing Latin inscriptions.

The coin’s extraordinary longevity—maintaining essentially the same weight and purity from Constantine until Emperor Alexios I Komnenos’ monetary reforms in 1092 CE—represents an unparalleled achievement in monetary history. Even after these reforms, modified versions continued circulating until Constantinople’s fall to Ottoman forces in 1453 CE, completing an astonishing thousand-year lifespan.

Design

The Solidus featured distinctive iconography that evolved from Roman imperial traditions into something uniquely Byzantine.

Early Solidi from Constantine’s reign maintained continuity with Roman tradition, displaying the emperor’s profile portrait on the obverse with Latin inscriptions detailing his titles and name. The reverse typically featured traditional Roman imagery such as Victory (the goddess of triumph) or other classical motifs, though Christian symbolism gradually appeared, reflecting Constantine’s pivotal role in Christianity’s legitimization.

As Byzantine culture evolved, so did the Solidus’ design. By the 6th century under Justinian I, the obverse typically showed a frontal portrait of the emperor wearing elaborate crown regalia and holding Christian symbols such as a cross or orb.

Reverse designs demonstrated even more pronounced evolution toward Christian symbolism. Images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, angels, and elaborate crosses replaced classical mythology and personifications.

Why the Solidus is Famous

The Solidus’ unprecedented stability—maintaining consistent weight and purity standards for over seven centuries—represents an achievement unmatched by any other currency.

The coin embodied Byzantine civilization’s unique synthesis of Roman imperial traditions, Greek cultural elements, and Christian religious identity. Its evolution from classical Roman imagery to distinctive Byzantine iconography provides a visual chronicle of this crucial transitional period in Western civilization—making it not just currency but a historical document in gold.

For medieval Europe, the Solidus represented the gold standard against which all other currencies were measured. It established the fundamental weight standard that influenced the florin, the ducat and other gold coins that would finance medieval and Renaissance Europe.

This thousand-year gold coin deserves its fame as one of history’s most influential and enduring currencies.

6. The Florentine Florin: Gold Coin of the Renaissance

History of the Florin

The Florentine Florin or fiorino d’oro was introduced in 1252 CE by the prosperous Italian city-state of Florence. It was the first European gold coin minted in significant quantities since the fall of the Western Roman Empire. This momentous monetary innovation coincided with Florence’s emergence as a dominant commercial and banking power during the early Renaissance.

The Florin’s introduction marked the end of Europe’s “gold drought”—a period of nearly five centuries when silver dominated Western European coinage while gold currency remained primarily Byzantine or Islamic. Florence’s ability to issue gold coins reflected both its growing economic might and its strategic trade connections.

The timing was significant. The mid-13th century saw an unprecedented commercial revolution sweeping through Italian city-states. International banking families like the Bardi, Peruzzi, and later the Medici were developing sophisticated financial instruments including bills of exchange, deposit banking, and double-entry bookkeeping. The Florin provided the physical monetary foundation for this financial innovation, facilitating larger transactions and international settlements.

The Florin’s weight (approximately 3.5 grams of nearly pure gold) and distinctive design remained remarkably consistent for over three centuries. Its reputation for reliability made it the preferred currency for major international transactions throughout Europe, with Florentine banking houses establishing branches from London to Constantinople. By the 14th century, the Florin had become so trusted that kings, popes, and merchant republics across Europe began issuing their own imitative gold coins based on its weight standard.

Even as Florence’s political influence declined in later centuries, the Florin’s monetary significance continued. Its weight standard influenced subsequent gold coins throughout Europe, including the Venetian ducat, Spanish escudo, and eventually the British guinea.

Design

The Florin featured a brilliantly simple yet distinctive design that remained essentially unchanged throughout its long history—a consistency that contributed significantly to its international recognition and acceptance.

The obverse displayed a large fleur-de-lis (lily flower), the heraldic symbol of Florence. This elegant, stylized lily was executed in relief with remarkable artistic detail, embodying both religious symbolism (the lily represented purity and was associated with the Virgin Mary, Florence’s patron) and civic identity. Around this central motif ran the Latin inscription “FLOR-ENTIA,” identifying the issuing city-state.

The reverse featured a standing figure of Florence’s patron saint, John the Baptist, depicted in Byzantine-influenced style wearing a hair shirt and cloak. The saint was shown with a halo, his right hand raised in blessing. The surrounding Latin inscription read “S[ANCTUS] IOHANNES B[APTISTA],” identifying the saint. This religious imagery provided spiritual authority to complement the civic symbolism on the obverse.

Unlike contemporary silver coins that typically displayed rulers’ portraits, the Florin’s design emphasized Florence’s republican identity during its initial period. The absence of a ruler’s image reflected Florence’s proud civic tradition as a self-governing commune (though later, when the Medici family effectively controlled the republic, the coin’s design remained unchanged as a matter of tradition and commercial trust).

The Florin’s consistent visual appearance, combined with its reliable gold content, created instant recognizability in international markets. Merchants throughout Europe could identify authentic Florins at a glance—a crucial advantage in an era of numerous competing currencies and frequent debasements by cash-strapped monarchs.

Why the Florin is Famous

As Western Europe’s first successful gold coin since late antiquity, it symbolizes the economic rebirth that accompanied the early Renaissance. This “return of gold” to European commerce facilitated larger transactions, international trade, and the sophisticated banking operations that would transform medieval economic systems into early capitalism.

For economic historians, the Florin represents a pivotal innovation that helped finance the Renaissance itself. Florence’s banking dynasties—particularly the Medici—used their florin-based financial networks to become history’s first international bankers, funding everything from papal operations to royal wars while simultaneously patronizing the artistic geniuses who defined Renaissance culture.

The coin’s influence extended far beyond Florence’s borders. Its weight standard was adopted by Venice for its ducat, by the Papal States, and eventually by numerous European monarchies, creating the first standardized international gold currency since the Byzantine solidus. This facilitated unprecedented commercial integration across late medieval and Renaissance Europe.

7. The Spanish Escudo: The Gold of Empire

History of the Escudo

The Spanish Escudo was introduced in 1537 by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who ruled as King Charles I of Spain. This new gold coin was created to finance Spain’s expanding imperial ambitions and to establish monetary uniformity across the vast Habsburg domains.

The Escudo (from Spanish for “shield”) initially weighed approximately 3.4 grams of 22-karat gold, and was intended to address the debasement of the previous coinage by introducing a coin with a standardised weight and fineness.

The Escudo was minted from the bounty of gold brought home from the New World. Just a few years earlier, Spanish conquistadors had overthrown the Aztec and Inca empires, gaining control of unprecedented gold and silver resources that would transform global economics.

By the mid-16th century, Spanish galleons were transporting vast quantities of precious metals across the Atlantic, funding Spain’s European wars and colonial expansion while triggering the “Price Revolution”—history’s first documented inflation caused by monetary supply increases.

The Escudo evolved into a family of related denominations, with the 2 Escudo piece (doubloon) becoming particularly prominent in international trade. By the early 17th century, larger denominations like the 8 Escudo piece (known as the “onza” or Spanish gold ounce) were regularly minted, particularly at colonial mints in Mexico City, Lima, Potosí, and later Bogotá.

The Spanish Empire’s extensive colonial network ensured the Escudo’s global reach. Spanish ships transported these coins across the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, establishing them as de facto international currency.

After nearly three centuries as the dominant gold coin in international commerce, the Escudo system was replaced in Spain by the Peseta in 1864, though colonial mints continued production for several more decades until Spain’s American empire collapsed. The Escudo’s legacy, however, continued through its direct influence on subsequent currency systems, including the United States’ early gold coinage.

Design

The Escudo’s design evolved significantly over its three-century history, reflecting Spain’s changing political dynasties and imperial aspirations while maintaining certain consistent elements that ensured its international recognition.

Early Habsburg-era Escudos under Charles V and Philip II featured the crowned Habsburg shield (which gave the coin its name) displaying the arms of the family’s various territorial possessions, including Castile, Leon, Aragon, Sicily, and Austria. The reverse typically displayed a cross potent, echoing the religious dimension of Spanish imperialism. Latin inscriptions proclaimed the monarch’s titles, often abbreviated due to space constraints but typically including “DEI GRATIA” (by the grace of God) and identifying the ruler as King of Spain and the Indies.

After the War of Spanish Succession brought the Bourbon dynasty to power in 1700, the design was modified to feature Bourbon heraldry while maintaining the shield motif. The cross potent was gradually replaced by a more elaborate cruciform design incorporating the castles and lions of Castile and Leon in the quadrants.

A significant design innovation came in 1732 under Philip V, when milled edges and more standardized designs were introduced as anti-counterfeiting measures. Later 18th-century issues featured increasingly refined portrait busts of Bourbon monarchs.

The final major design evolution occurred after 1772, when Charles III introduced the famous “portrait” or “bust” type Escudos featuring a remarkably lifelike royal portrait on the obverse and an elaborate shield with the Spanish arms on the reverse. These coins, particularly the 8 Escudo pieces, represent the artistic pinnacle of Spanish colonial numismatics.

Why the Escudo is Famous

The Spanish Escudo holds legendary status in monetary and world history as the first truly global currency. It represents the dramatic expansion of European influence that transformed world economics, politics, and culture during the Age of Exploration and Colonization.

These gold coins literally carried Spanish power and economic influence across oceans, becoming the preferred medium for international commerce from China to the Caribbean.

For historians and archaeologists, the Escudo provides invaluable insights into global trade networks and economic patterns. The discovery of Spanish gold coins in shipwrecks, buried hoards, and archaeological sites across five continents has helped map the extensive commercial connections that laid the foundations for our modern global economy.

The Escudo gained particular fame through its association with piracy and treasure hunting. The phrase “pieces of eight” (referring to the silver Real, but often conflated with gold Escudos in popular imagination) entered folklore through tales of buccaneers and buried treasure, while countless shipwrecks laden with Spanish gold have captured the imagination of treasure hunters from the 17th century to the present day.

In North America, the Escudo holds special significance as the primary gold currency circulating in colonial and early federal America. Spanish gold coins were so prevalent that they remained legal tender in the United States until 1857—more than half a century after American independence. The U.S. dollar itself was conceptually based on the Spanish 8 Reales silver coin, while early American gold coins were designed to be compatible with Spanish denominations already in circulation.

8. The British Gold Sovereign: The Victorian Standard

History of the Gold Sovereign

The modern British Gold Sovereign emerged in 1817 as part of a comprehensive currency reform following the Napoleonic Wars.

However, its lineage stretches all the way back to 1489 when Henry VII commissioned the original “sovereign”—a massive gold coin worth 20 shillings.

After a three-century hiatus, the Sovereign was reintroduced through the Coinage Act of 1816, which established Britain’s formal gold standard and created a new gold coin containing exactly 7.32 grams of 22-karat gold (0.2354 troy ounces of pure gold).

The Bank of England’s commitment to gold convertibility cemented London’s position as the world’s financial centre. As the British Empire expanded across continents, the Sovereign followed.

By the late 19th century, demand necessitated production beyond London, with branch mints established throughout the Empire: Sydney and Melbourne (1855), Perth (1899), Ottawa (1908), Bombay (1918), and Pretoria (1923).

World War I forced Britain to suspend the gold standard in 1914, but Sovereign production continued, though at reduced levels. The coin’s official role in British circulation ended with the Great Depression. Regular production resumed in 1957, continuing to the present day as a bullion coin but no longer as circulating currency.

Design

The Sovereign’s design combines artistic brilliance with patriotic symbolism in a package that became instantly recognizable worldwide. While the specifications remained remarkably consistent, the coin’s appearance evolved through several distinct phases.

The initial 1817 design featured an iconic depiction of St. George slaying the dragon. This dynamic composition showed the saint on horseback, sword raised dramatically after the fatal downstroke, the vanquished dragon writhing beneath the horse’s hooves. The reverse featured a portrait of George III with the Latin inscription “BRITANNIARUM REX FIDEI DEFENSOR” (King of the Britains, Defender of the Faith).

Over subsequent reigns, the obverse portrait changed to reflect the current monarch, evolving through distinctive versions of George IV, William IV, Victoria (in three major types: Young Head, Jubilee Head, and Old Head), Edward VII, George V, Elizabeth II (in five different portraits over her long reign), and most recently Charles III—creating a fascinating numismatic portrait gallery spanning over two centuries.

The reverse design alternated between St. George and various royal shield arrangements, depending on the period and denomination.

Technical specifications were maintained with remarkable precision: 22 carat gold (91.67% pure), 7.98 grams total weight, and 22.05mm diameter. This extraordinary consistency contributed significantly to the coin’s international acceptance and legendary reliability.

Why the Gold Sovereign is Famous

As the cornerstone of the British gold standard during the Victorian era, it physically embodied the economic might that made London the world’s financial centre and Britain the dominant global power. For nearly a century, the Sovereign served as de facto world currency.

For economists and historians, the Sovereign represents the gold standard at its most successful implementation. The Bank of England’s commitment to gold convertibility created unprecedented monetary stability that facilitated international trade and investment. The phrase “good as gold” reflected the absolute confidence that merchants worldwide placed in the Sovereign’s reliability.

The coin’s global influence extended far beyond British territories. Nations from Brazil to Egypt actively accumulated Sovereigns as central bank reserves, while international businesses accepted them for payment regardless of local currency systems.

9. The Louis d’or: The Sun King’s Gold

History of the Louis d’Or

The Louis d’Or (French for “Louis of gold”) was the dominant gold coin of the French monetary system of the Bourbon Kings. It was first minted in 1640 during the early reign of Louis XIII, when Finance Minister Cardinal Richelieu implemented sweeping monetary reforms to stabilize France’s chaotic currency system.

This gold coin would continue through multiple iterations under Louis XIV, Louis XV, and Louis XVI until it was discontinued in 1792 as a result of the French Revolution.

The Louis d’Or’s introduction marked France’s assertion of financial independence from Spanish monetary domination. Prior to 1640, Spanish gold—particularly the 8 Escudo piece—had served as the primary international gold currency. Richelieu’s monetary innovation aimed to establish French financial sovereignty while creating a stable domestic currency that would strengthen royal authority and facilitate taxation.

The coin achieved its greatest prominence during the 72-year reign of Louis XIV (1643-1715), the “Sun King,” whose unprecedented centralization of power transformed France into Europe’s dominant political, military, and cultural force.

Throughout its history, the Louis d’Or experienced several significant weight and composition adjustments (typically called “reformations”), reflecting the economic challenges facing the French monarchy. The original 1640 coin contained approximately 6.75 grams of 22-karat gold, but subsequent versions varied between 6.75-8.16 grams, with major reformations occurring in 1709, 1726, and 1785.

The Louis d’Or’s production ended dramatically with the French Revolution in 1792, when the revolutionary government replaced royal coinage with the decimal franc system. The coin’s final iteration, the “Constitutional” Louis (bearing Louis XVI’s portrait but struck in the name of the French nation rather than by divine right), represents a fascinating numismatic bridge between monarchical and revolutionary France.

Design

The original 1640 Louis XIII coins featured a laureate bust of the king on the obverse with the Latin inscription “LVDOVICVS XIII DEI GRATIA FRANCORVM REX” (Louis XIII, by the Grace of God, King of the Franks). The reverse displayed a simplified royal coat of arms with fleurs-de-lis, surrounded by decorative elements.

Under Louis XIV, whose remarkable 72-year reign saw the coin reach its apex of influence, the design evolved through several distinct types. Early issues maintained his father’s basic layout but showed the young king’s portrait. Beginning in 1679, a new design appeared featuring the now middle-aged Louis XIV’s portrait with flowing hair (often called the “à la mèche longue” type), while later issues showed his aging, more realistic likeness.

The most significant design innovation came in 1709 when Louis XIV introduced the famous “aux huit L” (eight L’s) reverse pattern—a cross formed by eight interconnected L-shaped devices (royal monograms) with fleurs-de-lis in the angles. This elegant geometric pattern represented a distinctly French interpretation of Baroque design principles and would influence French coinage for the next century. Subsequent monarchs maintained similar design structures but updated the royal portrait.

Why the Louis d’Or is Famous

As France’s premier gold coin during the nation’s ascension to European political and cultural dominance, the Louis d’Or embodied French royal power during its most magnificent expression.

For economists and historians, the Louis d’Or provides invaluable insights into the evolving financial structures that supported early modern state formation. The coin’s periodic “reformations” document the fiscal challenges facing even Europe’s wealthiest monarchy.

The coin achieved particular cultural significance through its association with the splendor of Versailles and the artistic flowering of French Baroque and Rococo styles.

The Louis d’Or’s legacy extends beyond numismatics into linguistic history—the term “louis” remained a colloquial French reference to money long after the Revolution abolished the actual coin, while its influence on subsequent European gold coinage can be seen in design elements and weight standards adopted by other national mints.

More broadly, the Louis d’Or represents the monetary foundation upon which French absolutism built its unparalleled cultural and political influence.

10. The Napoleon Gold Coin: Bonaparte’s Enduring Legacy

History of the Napoleon

The Napoleon gold coin emerged during one of history’s most dramatic political transformations, when revolutionary France was evolving into the Napoleonic Empire.

Formally introduced in 1803 as the 20 Franc gold piece, this coin would become universally known as the “Napoleon” after the man who dominated French history during its creation.

After abolishing royal currency in 1792, the revolutionary government established the decimal-based franc system. However, they struggled with paper currency hyperinflation during the Terror.

The Directory government reintroduced gold coinage in 1797, but it was Napoleon Bonaparte, as First Consul, who stabilized French currency through the landmark law of 17 Germinal Year XI (April 7, 1803), establishing gold and silver standards that would influence global monetary policy for the next century.

Napoleons were struck in denominations of 5, 10, 20, 40, 50 and 100 francs. But the term “Napoleon” is commonly associated with the 20 franc, which was 6.45g with 90% fineness.

Production continued across political regimes that followed Napoleon’s fall: the Bourbon Restoration, the July Monarchy, the Second Republic, the Second Empire, and the Third Republic, with each government modifying the coin’s design while maintaining its weight and purity standards. This remarkable consistency across disparate political systems—from empire to monarchy to republic.

The coin’s longevity made it a bedrock of European and global finance, with billions of francs worth of Napoleons circulating across continents and forming substantial portions of central bank reserves until the gold standard’s final collapse in the 1930s.

Design

The Napoleon featured designs that evolved significantly across various political regimes while maintaining certain consistent elements that ensured its international recognition.

The original Napoleonic issues (1803-1815) featured a right-facing portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte on the obverse, initially as First Consul and later as Emperor. These portraits showed Napoleon with short “Roman” haircut in the classical style, emphasizing his connection to ancient republican and imperial traditions. Inscriptions evolved from “BONAPARTE PREMIER CONSUL” to “NAPOLEON EMPEREUR,” tracking his political ascension. The reverse displayed “20 FRANCS” with the date in a wreath, surrounded by “RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE” (later “EMPIRE FRANÇAIS”), reflecting the regime’s republican origins despite its increasingly imperial nature.

Following Napoleon’s fall, the Bourbon Restoration (1814-1830) replaced his portrait with Louis XVIII and later Charles X, while maintaining the same weight standard—a tacit acknowledgment of the coin’s economic importance. The July Monarchy under Louis-Philippe (1830-1848) continued this tradition with updated royal portraiture.

The Second Republic (1848-1852) introduced a design featuring the head of Ceres (goddess of agriculture) by Jean-Jacques Barre, replacing monarchical imagery with republican symbolism while maintaining the established weight standard.

Napoleon III’s rise to power brought another imperial portrait to the obverse (1852-1870), first as a bare-headed portrait and later with a laurel crown after he declared himself emperor, directly invoking his uncle’s imperial legacy.

The Third Republic (1871-1940) returned to the Ceres design briefly before introducing the iconic “Angel Writing” design by Augustin Dupré in 1878. This famous version showed a winged genius (divine spirit) inscribing the French constitution on a tablet, symbolizing enlightened republican principles. This design, with minor modifications, would continue until regular production ceased.

Throughout these political transitions, the reverse consistently featured variations on a wreath motif containing the denomination and date, creating visual continuity despite changing obverse designs.

Why The Napoleon Is Famous

As France’s primary gold coin during a period of unprecedented political transformation, it physically embodied the nation’s economic continuity despite experiencing revolution, multiple republics, two empires, and several monarchies. This remarkable stability across political regimes demonstrated the coin’s fundamental economic importance.

The Napoleon gained particular fame through its association with Napoleon Bonaparte himself—one of history’s most consequential and controversial figures. As the financial foundation of the Napoleonic Empire, these coins financed the military campaigns, legal reforms, and architectural projects that fundamentally transformed Europe. When Napoleon’s Grande Armée marched across Europe, their payroll and supply purchases were largely funded through these gold coins.

For economists and historians, the Napoleon represents a pivotal innovation in monetary standardization. Its carefully calibrated specifications became the foundation for the Latin Monetary Union (1865-1927), history’s first major attempt at currency unification across multiple sovereign nations. This pioneering multinational monetary agreement established principles that would later influence the creation of the eurozone.

The coin achieved extraordinary geographic reach, circulating widely across Europe, the Middle East, North Africa, and colonies worldwide. Its reliability made it a preferred form of international payment and wealth storage, with many non-French banks and governments maintaining reserves of Napoleons rather than their own national gold coins.

The Napoleon’s legacy extends far beyond numismatics into global economic history. It established the 900/1000 gold fineness standard adopted by many nations, while its reliable specifications made it the model for modern bullion coins. Most significantly, it demonstrated how a well-designed monetary instrument could maintain stability and trust across multiple political regimes—a principle that would influence central banking practices into the modern era.

11. The Krugerrand: South Africa’s Revolutionary Bullion Coin

History of the Krugerrand

The Krugerrand is a 1oz gold bullion coin that was first minted in South Africa in 1967. It was the world’s first modern gold bullion coin explicitly designed for private investment. This revolutionary concept emerged during a period when private gold ownership remained restricted in many nations, including the United States (until 1974). South Africa, as the world’s dominant gold producer at the time, sought an innovative mechanism to market its gold internationally.

1oz is an accessible entry point for the individual and, while there were no alternatives, the Krugerrand dominated the market. This had a role in popularising gold ownership by individuals.

The timing was strategically significant. The post-war Bretton Woods monetary system was showing increasing strain, with the U.S. dollar’s gold convertibility becoming progressively more tenuous. As international investors sought hedges against potential currency devaluation, the Krugerrand offered a convenient, standardized vehicle for gold ownership.

While containing exactly one ounce of pure gold, the coin was actually struck in 22-karat gold (91.67% pure) with copper added for durability.

Despite the growing international anti-apartheid movement, which eventually led to sanctions against South Africa in the 1980s and import bans on Krugerrands in many Western nations, the coin achieved remarkable commercial success. By 1980, the Krugerrand accounted for 90% of the global gold coin market. An estimated 50 million Krugerrands have been minted since 1967, containing over 1,600 tons of gold.

The success of the Krugerrand inspired other countries to create their own investment grade bullion coins.

Design

The Krugerrand’s design balances South African national identity with practical considerations for a mass-produced bullion coin. Unlike most national gold coins before it, the Krugerrand’s design was deliberately utilitarian, emphasizing its role as an investment vehicle rather than artistic showcase or political propaganda.

The obverse displays a left-facing profile portrait of Paul Kruger, President of the South African Republic (Transvaal) from 1883 to 1900. This historically significant portrayal, shows Kruger with his characteristic long beard and stern expression. The image is surrounded by the country name in both official languages of apartheid-era South Africa: “SUID-AFRIKA” and “SOUTH AFRICA.”

As leader of the Boer resistance against British imperialism during the Second Boer War (1899-1902), Kruger represented Afrikaner nationalism and independence. However, his government’s policies also laid foundations for the later apartheid system, making the symbolism controversial for many observers.

The reverse features a springing springbok antelope—South Africa’s national animal. The year of minting appears divided on either side of the springbok, with the gold content “FYNGOUD 1 OZ FINE GOLD” stated below. Unlike most currency coins, no monetary denomination appears on the Krugerrand, as its value fluctuates with the daily gold price.

The coin’s distinctive golden-reddish hue results from its copper alloy content, distinguishing it visually from both traditional gold coins and modern competitors.

Why The Krugerrand Is Famous

As the world’s first modern bullion coin designed specifically for private investors, it created an entirely new category of monetary instrument. This democratized gold ownership at a critical moment in global financial history.

Before the Krugerrand, private gold investment typically required either costly numismatic coins at high premiums or commercial bars. The Krugerrand’s innovation was combining investment-grade gold in a convenient, standardized, easily recognizable form that traded close to its intrinsic metal value.

The coin’s global impact extends far beyond South Africa’s borders. Its phenomenal commercial success directly inspired the creation of competing national bullion coins, including the:

- Canadian Maple Leaf (1979)

- American Eagle (1986)

- British Britannia (1987)

- Australian Kangaroo (1986)

- Chinese Panda (1982)

Virtually every major gold-producing nation now issues bullion coins following the template the Krugerrand pioneered.

12. The Canadian Maple: The Premier Modern Bullion Coin

History of the Gold Maple

The Canadian Gold Maple Leaf was first introduced by the Royal Canadian Mint in 1979, during a time of significant global economic uncertainty. The coin was created as a direct response to the South African Krugerrand’s dominance in the gold bullion market and international sanctions against South Africa’s apartheid regime, which had limited the availability of gold coins to investors worldwide.

The late 1970s saw rampant inflation, political instability in the Middle East, and growing concerns about the global monetary system. Canada, with its stable government and abundant natural resources, positioned itself as a reliable source of investment-grade gold at a time when investors desperately sought safe havens for their wealth.

Initially produced with a gold purity of 99.9%, as opposed to the 91.67% purity of the Krugerrand, the Royal Canadian Mint raised the standard to 99.99% in 1982, making it the first government-issued gold bullion coin to achieve this exceptional level of purity.

In 2007, the Mint pushed boundaries even further by creating special edition Maple Leafs with an astounding .99999 (99.999%) purity, cementing its reputation for producing the purest gold coins in the world.

Design

The design of the Canadian Gold Maple Leaf is strikingly simple yet elegant, embodying Canadian national identity through its iconic imagery. The obverse features the effigy of Queen Elizabeth II, which has been updated three times throughout the coin’s history to reflect the aging monarch. Since her passing, King Charles III’s profile has been featured on new minting runs.

The reverse side displays the coin’s namesake symbol – a meticulously detailed single maple leaf, Canada’s most recognizable national emblem. The engraving is so precise that even the delicate veins of the leaf are clearly visible, showcasing the Mint’s exceptional craftsmanship.

The maple leaf design has remained largely unchanged since the coin’s introduction, creating a consistent and instantly recognizable appearance that has become synonymous with Canadian gold.

The coin’s design includes several sophisticated security features, particularly in more recent mintings. In 2013, the Royal Canadian Mint introduced a small privy mark in the form of a textured maple leaf micro-engraved with the year of issue, visible only under magnification. In 2015, precision-cut radial lines were added to both sides of the coin, creating a light-diffracting pattern that makes counterfeiting extremely difficult. These security innovations demonstrate the Mint’s commitment to protecting the integrity of the Maple Leaf in the modern era.

Why the Gold Maple is Famous

First and foremost the Maple is known for its exceptional purity. When most gold coins were being produced at 22-karat (91.67%) purity, the Maple Leaf set a new standard at 24-karat (99.99%) pure gold. This unprecedented level of purity captured the attention of investors and collectors worldwide, particularly in Asian markets where higher gold purity is especially valued.

The coin’s significance extends beyond its material composition. It represented Canada’s emergence as a major player in the global precious metals market.

The Maple Leaf has also been at the forefront of numismatic innovation. In 2007, the Royal Canadian Mint created the world’s first million-dollar coin – a 100 kg, 99.999% pure gold Maple Leaf with a $1 million face value, showcasing the mint’s technical capabilities and flair for the spectacular. In 2013, the Mint pioneered new anti-counterfeiting technology specifically for the Gold Maple Leaf, setting standards that other mints would later follow.

Through economic booms and recessions, the Canadian Gold Maple Leaf has maintained its status as a premier investment vehicle and a symbol of Canadian craftsmanship and quality, making it truly one of the most famous gold coins in modern numismatic history.

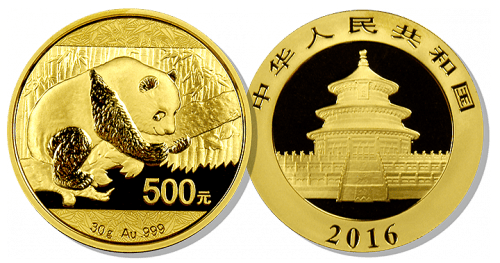

13. The Chinese Gold Panda: The PRC’s Golden Ambassador

History of the Gold Panda

The Chinese Gold Panda was first introduced in 1982 by the People’s Republic of China, marking a significant milestone in China’s re-emergence as an economic power.

Before the Gold Panda’s creation, China had limited participation in the international gold market, with strict government controls on gold ownership and trading.

The launch of this coin represented a strategic decision by Chinese authorities to establish a presence in the growing global bullion market, while also showcasing Chinese craftsmanship and cultural heritage to the world.

Initially minted at the Shenzhen Guobao Mint, production later expanded to include several other Chinese mints including those in Shanghai, Shenyang, and Beijing.

Design

The Chinese Gold Panda’s design philosophy represents a fascinating departure from most other sovereign bullion coins. While the reverse of most national gold coins maintains a consistent design year after year, the Gold Panda features a new panda design annually. This annual change has created a collector’s phenomenon, with enthusiasts eagerly anticipating each year’s new artistic interpretation.

The obverse of each coin showcases the Temple of Heaven (Tiantan) in Beijing, one of China’s most iconic architectural treasures and a UNESCO World Heritage site. The temple’s Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests is depicted in exquisite detail, with the inscription “People’s Republic of China” in Chinese characters above it.

The reverse side features the coin’s namesake – the giant panda, China’s beloved national animal and a globally recognized symbol of conservation efforts. Each year’s panda design captures these charismatic animals in different natural settings and poses – whether playfully climbing bamboo, caring for cubs, or simply lounging in their natural habitat.

Why the Gold Panda is Famous

The Chinese Gold Panda pioneered the concept of annual design changes for a major government bullion coin. This innovative approach transformed the Gold Panda from a mere investment vehicle into a collectible series, with each year’s release generating excitement and anticipation among numismatists worldwide. Some years’ designs have become particularly iconic.

The Gold Panda also represents China’s cultural diplomacy through numismatics. During a period when China was still relatively closed to foreign visitors, these coins served as ambassadors of Chinese culture, showcasing the nation’s artistic traditions and natural heritage to international audiences. The panda itself, as a symbol of Chinese conservation efforts and international goodwill (through China’s “panda diplomacy”), reinforces this cultural significance.

From an investment perspective, the Gold Panda achieved something remarkable – it successfully bridged Eastern and Western precious metals markets. The coin gained acceptance in Western investment circles while maintaining strong demand in Asian markets, particularly Japan, Singapore, and Hong Kong, where collectors have shown a particular enthusiasm for the series. This cross-cultural appeal has ensured consistent demand and liquidity.

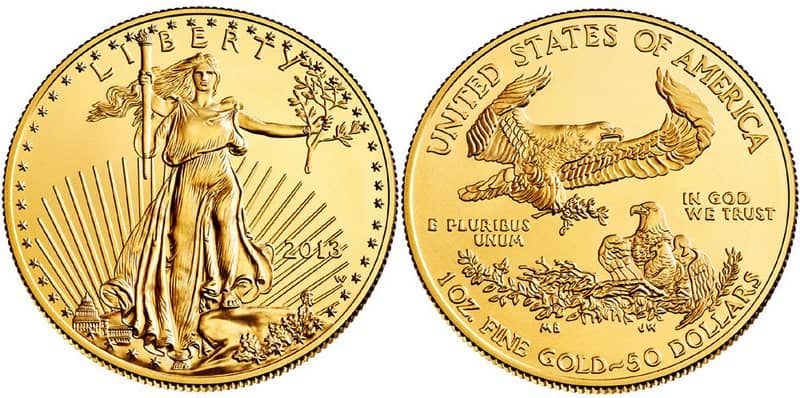

14. The American Gold Eagle: The Iconic Modern Bullion Coin

History of the American Gold Eagle

The American Gold Eagle was first introduced in 1986. It was part of the United States’ ambitious Gold Bullion Coin Act of 1985, legislation that marked America’s return to gold coinage after a long hiatus.

The timing of this introduction was significant, coming during the Reagan administration’s economic policies. It also represented a renewal of American interest in physical gold ownership following the termination of the gold standard in 1971 and the lifting of the private gold ownership ban in 1974.

Initially, the American Gold Eagle was produced in four denominations: 1 ounce ($50 face value), 1/2 ounce ($25), 1/4 ounce ($10), and 1/10 ounce ($5).

Unlike some other national gold bullion coins that prioritize purity, the Gold Eagle was deliberately created with a composition of 91.67% gold (22 karat), with the remainder being silver (3%) and copper (5.33%). This alloy composition was chosen to increase the coin’s durability for circulation, following the long-standing American tradition of creating gold coins resilient enough for regular handling.

The United States mint also responded to the market demand for a 99.99% gold coin by producing the Gold Buffalo in 2006.

Design

The American Gold Eagle’s design draws directly from one of the most celebrated artistic achievements in American numismatic history: Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Lady Liberty, originally created for the double eagle ($20 gold piece) of 1907. President Theodore Roosevelt had personally commissioned Saint-Gaudens to create this design as part of his initiative to beautify American coinage, considering the previous designs to be artistically inadequate for a great nation.

The obverse features Lady Liberty in full-length figure, her hair flowing in the wind as she strides confidently forward from the nation’s capital. She holds a torch in her right hand, symbolizing enlightenment, and an olive branch in her left, representing peace. The sun’s rays emanate from the lower left, and fifty stars encircle the design, representing the states of the Union. The date is displayed in Roman numerals on the original Saint-Gaudens design, but appears in standard Arabic numerals on the Gold Eagle.

What makes this design particularly significant is both its artistic merit and its symbolic power. Lady Liberty is portrayed not as a static, idealized figure but as a dynamic force moving forward – an embodiment of American progress and optimism. Art historians have noted Saint-Gaudens’ incorporation of classical Greek influences while creating something distinctly American in spirit.

The reverse of the original Gold Eagle (1986-2021) featured a design depicting a male eagle carrying an olive branch as it descends to a nest containing a female eagle and hatchlings. This family scene was specifically chosen to represent American family values and unity during the Reagan era.

In 2021, the reverse design was replaced with a portrait of an eagle, focusing on a detailed, naturalistic depiction of an eagle’s head in striking detail. This new design continues the American tradition of featuring the national bird while bringing a contemporary aesthetic to the historic coin.

Why the Gold Eagle is Famous

The American Gold Eagle has established itself as one of the most liquid and widely recognized gold bullion products in the world. Its widespread acceptance in international markets means that Gold Eagles can be bought and sold easily across borders, often with minimal spreads between buying and selling prices. This liquidity has made it a cornerstone of many investment portfolios.

The unique 22-karat composition of the Gold Eagle also contributes to its fame. While other modern bullion coins pursued ever-higher purity levels, America deliberately chose the traditional English standard of 22-karat gold, creating a more durable coin that honors the composition used in American gold coins since the Coinage Act of 1792. This distinctive approach sets the Gold Eagle apart in the global market.

The Gold Eagle’s cultural impact extends into American financial consciousness, with the coin frequently featured in discussions of sound money, inflation hedging, and portfolio diversification. It has become a symbol of financial prudence and independence in uncertain times, reinforcing its status as not just a famous coin but an American icon of enduring value.

Lessons From A Study Of Famous Gold Coins

1. Gold Coins Reflect the Economic Values of Their Time

Famous gold coins often emerge during periods of monetary strength, national pride, or economic upheaval. Studying these coins helps historians understand when societies leaned on gold to symbolize stability and trust and when they didn’t.

2. Political Power and Monetary Policy Are Intertwined

From Roman aurei to British sovereigns, the images and inscriptions on gold coins often project political authority. They reveal how emperors, kings, and republics alike used coinage to legitimize rule, control economies, and unify people under a shared symbol of value. Since I’m a conservative and not a libertarian or anarcho-capitalist I actually enjoy thinking about how state power is projected through coinage.

3. Cultural Identity Is Minted in Gold

National symbols—like the eagle, Britannia, or Krugerrand’s springbok—show how deeply gold coins reflect cultural pride and myth-making. The choice of imagery tells us what a nation wanted to project both inward and outward during that era.

4. Hard Assets Endure Where Fiat Fails

Despite fiat systems dominating today’s economies, famous gold coins continue to attract collectors, investors, and historians because they represent enduring value. These coins teach us that when paper currencies fail or inflate, people instinctively return to trusted, tangible money.

Conclusion

From the ancient world, to the medieval world, to the modern world, to the bullion coins of the fiat era each and everyone of these famous gold coins has a story to tell.

Each was produced in a particular set of historic and economic circumstances and reflects a particular chapter of monetary history.

But these coins are far more than relics of economic history — they are enduring symbols of a time when money was backed by something real, tangible, and trusted.

In an age of digital money and central bank experimentation, the legacy of gold coins reminds us that trust in money must be earned — and that sometimes, the past has the clearest message for the future.

To your protection and prosperity,

Thomas

P.S. Have I left out anything important? Please let me know. Or if you found this information to be of high value, drop me a line, too. I love hearing from readers.

Image Credits

Famous Gold Coins by Zlataky on Unsplash

Lydian Stater is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0

Croeseid is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

Persian Daric is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.5

Gold Aureus is in the public domain

Solidus is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

Florentine Florin is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.5

Spanish Escudo is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0

British Gold Sovereign is in the public domain

Louis d’or is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0

Napoleon is in the public domain

Krugerrand is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

Canadian Maple by Zlataky on Unsplash

Gold Panda is licensed under CC-BY-SA 4.0

Gold Eagle is licensed under CC-BY-SA 3.0